Because Ohio has expanded Medicaid under the ACA, low-income adults without dependent children have been eligible for coverage since 2014. The following residents can enroll in Medicaid in Ohio (immigration rules apply, and the following income limits include the built-in 5% income disregard that’s added to the regular income limits when determining income-based Medicaid eligibility):

Certain low-income people who are blind, disabled, or age 65+ can enroll in Ohio Medicaid, but these populations must also have low asset/resource levels to qualify for Medicaid. 1

Federal poverty level calculatorof Federal Poverty Level

You can enroll online at HealthCare.gov or at the Ohio Benefits website. You can also enroll by phone at 1-800-318-2596 or 800-324-8680.

Eligibility: Adults are eligible with incomes up to 138% of poverty. Children are eligible with incomes up to 206% of poverty, and pregnant women are eligible with incomes up to 200% of poverty.

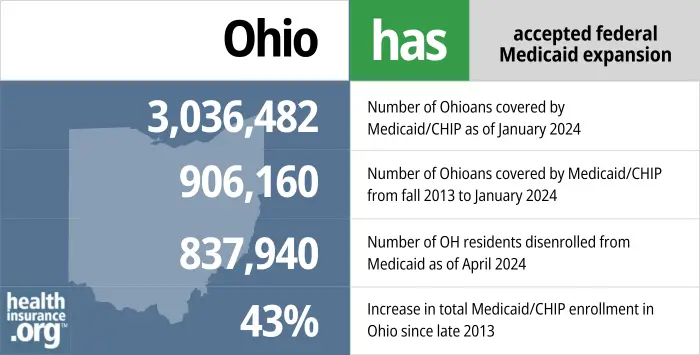

In 2013, Ohio’s then-Governor John Kasich announced that the state would expand Medicaid. Ohio lawmakers who were opposed to Medicaid expansion brought a lawsuit against the Kasich administration to block Medicaid expansion, because the full legislature was not involved in the decision to expand Medicaid. Instead, it was done through the Controlling Board (a group of legislators who handle budget adjustments in the state — most states do not have something like this) after the Ohio House and Senate both voted to block Medicaid expansion and Kasich vetoed their measure.

Ultimately, in late 2013, the Ohio Supreme Court ruled in favor of Governor Kasich, and Medicaid expansion took effect as scheduled in 2014. During the 2015 legislative session, lawmakers agreed to allow Medicaid expansion to continue, although the issue was just part of the budget agreement – there was no separate legislation on Medicaid expansion.

enrollment in Ohio since late 2013. " width="700" height="355" />

enrollment in Ohio since late 2013. " width="700" height="355" />

We’ve created this guide to help you understand the Ohio health insurance options available to you and your family, and to help you select the coverage that will best fit your needs and budget.

Hoping to improve your smile? Dental insurance may be a smart addition to your health coverage. Our guide explores dental coverage options in Ohio.

Use our guide to learn about Medicare, Medicare Advantage, and Medigap coverage available in Ohio as well as the state’s Medicare supplement (Medigap) regulations.

Short-term health plans provide temporary health insurance for consumers who may find themselves without comprehensive coverage.

Enrollment in Medicaid is year-round; you do not need to wait for an open enrollment period if you’re eligible for Medicaid

Many Medicare beneficiaries receive Medicaid’s help with paying for Medicare premiums, affording prescription drug costs, and covering expenses not reimbursed by Medicare – such as long-term care.

Our guide to financial assistance for Medicare enrollees in Ohio includes overviews of these benefits, including Medicare Savings Programs, long-term care coverage, and eligibility guidelines for assistance.

Between February 2020 and early 2023, Ohio’s Medicaid enrollment grew by more than 737,000 people, due to the pandemic-related continuous coverage rules. States were allowed to resume Medicaid disenrollments starting in April 2023, and could begin the process of starting to redetermine eligibility as early as February 2023.

Ohio opted for that timeline, so the first round of renewals began to be processed in February 2023. But the first round of disenrollments came at the end of April, meaning that the first month any Ohio Medicaid enrollees needed to have other coverage in place was May 2023. By December 2023, more than 609,000 Ohio residents had been disenrolled from Medicaid. 5

Ohio enacted an appropriations bill in 2021 that contained some guidance in terms of how eligibility redeterminations should be handled after the pandemic. But the state had to modify some of those provisions to abide by federal rules for the “unwinding” and return to normal eligibility processes. Federal rules require states to spread out eligibility redeterminations such that no more than one-ninth of a state’s enrollees go through renewal each month, so Ohio cannot redetermine eligibility as quickly as they had initially planned. But the state prioritized renewals for people who are most likely to no longer be eligible for Medicaid, which is allowed under federal guidelines; Ohio hired a third-party vendor to help identify these enrollees.

Enrollees who are notified that they’re no longer eligible for Medicaid will be able to appeal that decision if they believe that they are still eligible. But for those who are no longer eligible, other coverage options are available: An employer’s plan, a plan obtained through the exchange/marketplace (HealthCare.gov), or Medicare, depending on the person’s circumstances. A special enrollment period is available for all of these coverage options, due to the loss of Medicaid.

CMS reported that 64,738 Ohio residents had transitioned from Medicaid to an Alabama Marketplace health plan by October 2023. 6

As of late 2023, total Medicaid/CHIP enrollment in Ohio stood at more than 3.15 million people, which was up 48% from 2013, before the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid took effect (nationwide Medicaid enrollment is up 52%, so Ohio’s enrollment growth is very similar to the national average). 7

And nearly 850,000 of those enrollees have coverage as a result of Ohio’s expansion of Medicaid under the ACA (this population is referred to as Group VIII, or the expansion group). 8

Medicaid enrollment, including Group VIII and other eligibility categories, grew significantly during the COVID pandemic This is partially due to the widespread job and income losses, particularly in the early days of the pandemic. But was also driven in large part by the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, which provided states with additional federal Medicaid funding on the condition that Medicaid enrollees not be disenrolled during the COVID public health emergency. That rule ended on March 31, 2023, and Ohio returned to normal eligibility redeterminations and disenrollments in April 2023. As noted above, more than 609,000 Ohio residents had been disenrolled from Medicaid by December 2023.

In its 2018-2019 fiscal year budget, the Ohio legislature required the state to seek federal approval for a work requirement that would apply to the Medicaid expansion population. Although then-Gov. Kasich vetoed several items in the budget that applied to Medicaid, he did not veto the work requirement provision.

Ohio’s work requirement proposal was submitted to CMS in April 2018, with an estimate that 18,000 people would lose coverage due to non-compliance with the work requirement or reporting requirements. Although the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) approved the waiver in May 2019, it was never implemented. Ohio had planned to implement the work requirement at the start of 2021, but it was delayed as a result of the COVID pandemic. In August 2021, CMS officially withdrew the waiver approval. The state appealed that decision, but Medicaid work requirement waivers were universally rejected or withdrawn by the Biden administration.

It’s noteworthy that a few months after the state’s proposal was submitted to CMS, the Ohio Department of Medicaid published an extensive report on Medicaid expansion, which included the fact that 98.3% of people continuously enrolled in Ohio’s expanded Medicaid “were either employed, in school, taking care of family members, participating in an alcohol and drug treatment program, or dealing with intensive physical health or mental health illness (many had comorbid conditions).” In other words, this confirms the idea that the vast majority of the state’s expanded Medicaid population was either already in compliance with what the work requirement would entail, or would be exempt from it. (The state estimated that about 36,000 expansion enrollees would have had to start working or enroll in job training, education, or certain volunteer activities, for a combined total of at least 20 hours per week, to avoid being disenrolled from Medicaid.)

Critics contend that Ohio’s work requirement for SNAP benefits (on which the proposed Medicaid work requirement is closely modeled) has resulted in significantly fewer Ohio residents receiving food assistance, but has not improved their employment situation. Instead, reliance on food banks and soup kitchens has increased sharply, and food instability is more of a problem than it was before the work requirement was implemented for SNAP. Advocates worried that the same thing would happen with Medicaid — a work requirement doesn’t give people better employment prospects, but it puts their health coverage in jeopardy, potentially making it that much harder for them to hold down a job.

Ohio’s former Gov. John Kasich was not a fan of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), but he was one of the few Republican governors who supported the ACA’s Medicaid expansion component early in the process, and Ohio’s Medicaid expansion took effect as called for in the ACA, in January 2014. Kasich remained steadfastly supportive of Medicaid expansion, including during his presidential campaign in 2015.

In early January 2017, Republican lawmakers began taking steps to repeal the ACA. Kasich warned his fellow Republicans that repealing the ACA — without an equally robust replacement — could be disastrous. He pointed to the hundreds of thousands of Ohio residents who had gained coverage as a result of Medicaid expansion, and asked Republican lawmakers to explain exactly how those folks would continue to access coverage and healthcare without Medicaid expansion.

Kasich also noted that Medicaid expansion in Ohio played a key role in the state’s fight against opioid abuse, as people — who would otherwise have been uninsured — have been able to receive rehabilitation services covered by Medicaid.

Kasich was term-limited and could not run for reelection in 2018. Republican Mike DeWine won that election, narrowly defeating Democrat Richard Cordrey. Although DeWine had been critical of Medicaid expansion in the past, he had embraced it by mid-2018, vowing to keep the expanded eligibility guidelines in place as governor.

Lawmakers in Ohio came to a compromise on their budget bill in June 2017 and sent it to Governor Kasich. The Senate’s version of the bill had included a freeze on new Medicaid expansion enrollments after July 1, 2018, and that provision remained in the bill after it went through the conference committee process to reconcile the differences between the House and Senate versions of the budget.

Kasich had noted that the Medicaid expansion freeze would result in 500,000 people losing coverage in the first 18 months, since people would lose coverage if their income increased and would then be unable to get back on Medicaid if their income subsequently decreased (income volatility is particularly common among low-income populations).

Kasich used his line-item veto power to eliminate the Medicaid expansion freeze, and he also vetoed a provision that would have required Medicaid expansion enrollees to pay monthly premiums (in the form of health savings account contributions) for their coverage. Monthly premiums for Medicaid expansion populations require approval from CMS; the Obama Administration only approved limited premium requirements, and rejected a more far-reaching premium requirement that Ohio had proposed in 2016 (details below). But the Trump Administration made it easier for states to impose these types of requirements on Medicaid expansion enrollees.

On July 6, 2017, lawmakers in the House overrode Kasich’s veto of the provision that would have required Medicaid expansion enrollees to make health savings account contributions, but they did not vote to override his veto of the Medicaid expansion freeze (the Senate would also have to agree on the veto override for it to be successful, but could not vote until the House did so). In all, the House overrode 11 vetoes (most of which pertained directly to Medicaid) although the Senate only agreed to override six of those items — including a provision that allows the state legislature to determine whether additional optional populations will have access to Medicaid in Ohio, instead of allowing the Ohio Department of Medicaid to make decisions about populations whose eligibility is optional under federal Medicaid rules.

The proposed Medicaid premiums (health savings account contributions) in the House’s veto override would have been part of a “Healthy Ohio” program that was initially proposed in 2016 but did not receive approval from the Obama administration (in 2016, Ohio was requesting permission to charge premiums even for enrollees with income below the poverty level, which is not part of their 2018 budget proposal; see below for details about the 2016 proposal). However, the Trump administration made it clear that they were more likely to grant Medicaid waiver flexibility to states, even when the outcome was likely to be fewer people covered.

If it had been approved by state lawmakers and the federal government, the “Healthy Ohio” program would have required non-pregnant, childless adults with income above the poverty level (i.e., between 100-138% of the poverty level) to pay premiums, averaging about $20 per month (but not more than 2% of household income), for their coverage. This type of premium arrangement had already been allowed in some other states under the Obama administration. However, the Senate did not vote to override Kasich’s veto of the proposed Healthy Ohio premiums, so the provision did not advance.

The Ohio House still had the option to vote to override Kasich’s veto of the Medicaid expansion freeze later in the year, and they considered that possibility in September 2017, but ultimately did not move forward with a vote in 2017.

In September 2016, CMS denied the Healthy Ohio waiver proposal that would have required all enrollees (including those with income below the poverty line) to pay 2% of their income (but no more than $99 per year) into a health savings account. The problem for CMS was that the new guidelines would have resulted in people losing their Medicaid coverage if they got more than 60 days behind on their health savings account payments, and they would have had to get caught up on the payments to be able to re-enroll in the coverage.

The state estimated that 125,000 people would lose coverage under the new guidelines, which was a non-starter for CMS — particularly because the state wanted to bar people from re-enrolling until they paid their overdue contributions.

The budget that lawmakers in Ohio passed in June 2017 called for the state to submit a waiver to CMS asking for permission to charge premiums for Medicaid, but only for enrollees with income above the poverty level. Governor Kasich vetoed this provision, but lawmakers in the House overrode his veto. However, the Senate did not vote to override the veto, so Ohio did not move forward with submitting a new waiver proposal to CMS.

Ohio enacted Medicaid in July 1966, just six months after the earliest states to do so. The state implemented CHIP (Children’s Health Insurance Program) in 1998, initially covering children up to age 19 with household income up to 150% of poverty (that upper threshold was later increased to 200% of poverty).

The federal government pays 67% of the cost of Ohio’s traditional Medicaid program, and the state pays the remainder. But the state gets a far better deal when it comes to Medicaid expansion: For 2014 – 2016, the federal government paid 100% of the cost of covering the population that was newly eligible under the ACA’s Medicaid expansion guidelines. That percentage eventually declined to 90% as of 2020, but it remains at that level going forward, with the state never paying more than 10% of the cost of covering the Medicaid expansion population.

In 2011, Governor Kasich created the Ohio Governor’s Office of Health Transformation to “modernize Medicaid, streamline health and human services programs, and pay for value.”

And although the ACA’s Medicaid expansion took effect in January 2014 in Ohio (as it did in all states that were early adopters of Medicaid expansion), the state also used a Section 1115 waiver to expand Medicaid in 2013 to cover 30,000 non-elderly adults in Cuyahoga County. The eligibility threshold extended to 138% of the poverty level (the same as the ACA guidelines), so unless they had a change in income during the year, those early enrollees were able to transition to regular Medicaid expansion starting in 2014.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.